A Brief History of Science Fiction Film Music

References, Links, and Works Cited

Created by Jessica Rooney

Last updated 5/1/06

Overview

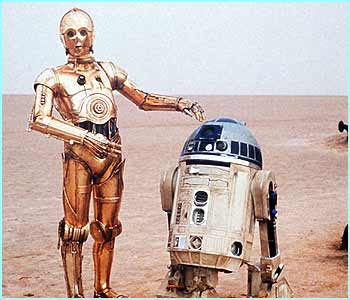

Science fiction films bombard the viewer with the fantastic. Spaceships roar over a grey desert crawling with bounty hunters, enormous bison-like pack animals, and outlaws hiding there long blue noses beneath deep hoods. A leather-clad woman makes an impossible leap from the roofs of two buildings, chased by a computer program that can take over other bodies and defy all natural laws at will. A youth looks pensively at low hanging twin suns, not knowing that he will be the one to redeem the hopes of a rebel army. Exhausted with the hardships of living in reality, a man betrays his companions so that he can once again enjoy the comforts of slavery in a fabricated world. Yet while all these scenes are extraordinary, what is even more amazing is that an audience is expected to take all of these images as real.

As a genre based upon a mixture of “actual, extrapolative, or speculative science” and “social context[s] with the lesser emphasized, but still present, transcendentalism of magic and religion” (Sobchack 63), science fiction authors are greatly challenged to make audiences suspend their disbelief and accept situations as real. This striving for verisimilitude is further complicated when science fiction is taken to the screen. Film is the “most iconic of the various artistic languages” (Brown 16) and relies on audiences removing their own acknowledgement of being in a theatre to fully accept what is happening on the screen as real. Yet while it may be easier for an audience to forget their own personal realities when the characters on screen are going through everyday, realistic situations, the inclusion of the impossible and highly unlikely in science fiction films makes it even harder for audiences to truly believe in the plot and characters and thus make the film an artistic success.

One way science fiction films try to achieve audience participation is through the use of spectacle such as “action and suspense to entertain the audience…over more subtle plot elements” (“Science Fiction Film”). But an even stronger tool science fiction films can use is to make the characters and situations recognizable to the audience is to appeal to the audience’s emotions. This can be done most obviously through character and story development, but music can also serve to this end very effectively.

In the original days of the motion pictures, it was considered that music was needed to “psychologically…smooth over natural human fears of darkness and silence” (Brown 12). Today, music still serves a large psychological factor in films, but it has moved far beyond its original simple use to quell fear. Firstly, music allows audiences to connect more directly to the characters of a film. When an audience sees an image on a screen, what they are viewing is filtered and removed from their own experience because the images are isolated in a world completely separate from the audience. Yet when an audience hears music in a film a direct response occurs because the music can exist in both the film world and the real world that the audience is sitting in. As Mark Evans states, “while vision creates a ‘there’…sound creates a ‘here’, or rather a ‘there’ + ‘here’, two points in space, the object and the subject, both separated and connected by the vibrating medium which transmits the sound” (190). Therefore, unlike other aspects of film, music can elicit a direct emotional experience from the audience without having to work through a character. Because the audience is then personally experiencing the same type of emotions of a character they can “grasp, realize, comprehend, these feelings, without pretending to have them or imputing them to anyone else” (Brown 27). This allows the audience to feel like they understand the characters, even if the characters are completely foreign to their own realities and experiences, which is especially important in science fiction films. This can in turn make situations seem more believable as an audience reasons that because what they are feeling is true the conditions producing the feeling must therefore also be real.

Music can also elicit emotions and audience interaction without relying on characters. Music can make environments seem to be real because it can give emotion to a visual scene and turn it from a static viewing to a dynamic experience that the audience participates in. Even if an audience does not trust what is being presented to them on a screen they can not help but trust their own feelings, and because music gives rise to real feelings it creates validity in a scene. Once this occurs all the other parts of an environment are made more believable, for “by forming an interactive whole in which the spectator can become totally immersed, the separate components [or a scene] become more palatable” (Brown 25). Yet while music can make a completely unrecognizable scene seem familiar, and it can also make something that would seem to be identifiable seem foreign. For example, if a scene supposedly depicting an alien world is shot in a desert, music can help turn audience attention from recognizing the scenery because it can create feelings and reactions that the audience normally wouldn’t experience in that landscape. By imposing true emotions that are usually unconnected to an environment, that environment is changed in the audience’s mind into a new place altogether.

Similarly, music can help direct emotional responses and make sense of visual images and plot components, especially foreign ones that the audiences doesn’t instinctively know how to respond to. Audiences trust music because as a recognizable and ingrained component of culture, music creates a ““logical picture” of sentient: and can serve as “a source of insight” (Brown 26). Therefore, through cues such as leitmotifs, various types of orchestration, and theme development, the audience can have a sense of what is ‘good’ and ‘bad.’ This in turn allows the audience to be on the same (if not greater) level of perception as the characters. Music is the substitute to the experiences, history, and culture the characters have experienced, and so “music provides a foundation in affect for narrative cinema’s visual images” (Brown 26), helping the audience feel included in the weave of the film itself.

Because of the ability of music to create connecting emotion, make situations believable, create recognizable or unfamiliar environments, and direct audience response to new scenarios, it plays a vital role in science fiction film. Music helps to bridge the gap between disbelief and acceptance in science fiction films, making them believable, even if only for the two hours that the audience views them in a theatre. This website will be focusing on how these abilities of film music have been used in two films, Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) and The Matrix (1999), as well as looking at the history of science fiction film music.