|

||||||||||

|

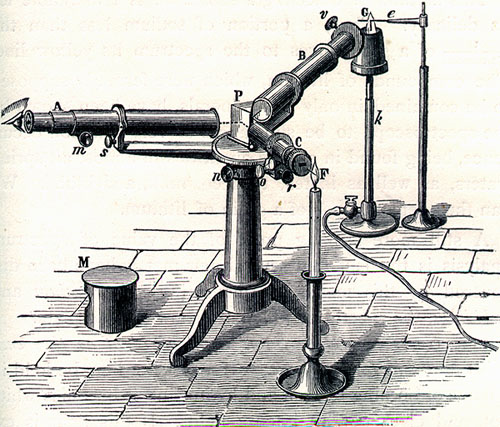

The Astronomers of Mars When Martian science fiction was primarily affected by astronomers, it was done so by those in the west as early science fiction is (and still is) predominantly European and American. Although the first science fiction about Mars was not written until 1880 in Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac, astronomers from the 17th century till the days of the Mariner, Mars, and Viking missions primarily influenced the imagination of science fiction authors. I also included Lowell and Schiaparelli’s drawings, along with a captioned picture of a spectroscope.

Giovanni Cassini (1625-1712) did not dedicate a lot of time to Mars, but in 1644 he became the first to depict it with a landscape. He was not the first to recognize Mars as being a celestial body rather than a dot in the sky, but he was the first to draw it as such. (Left) Dutch astronomer Christiann Huygens (1629-1695) used Cartesian thought to reason that life could exist on Mars. He published his beliefs about similarities beween Mars and Earth in Cosmotheros. Huygens’ Martians reflect his anthropocentric views: they resemble humans and even are god fearing. (Above Right)

Besides co-discovering Helium, Pierre Jannssen (1824-1907) postulated that Mars had an atmosphere because he detected water vapor on mars through a spetroscopic analysis. He claimed this in spite of knowing the conditions at Mr. Etna (in Sicily), where took the measures, were not ideal.

This is a spectroscope, the use of which either suggested life on Mars or did not. As alluded to, this instrument was the source of many arguments about the Martian climate and atmosphere.

Schiaparelli’s Canali Lowell's Canals

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Website Last Updated 12/2/09 | ||||||||||

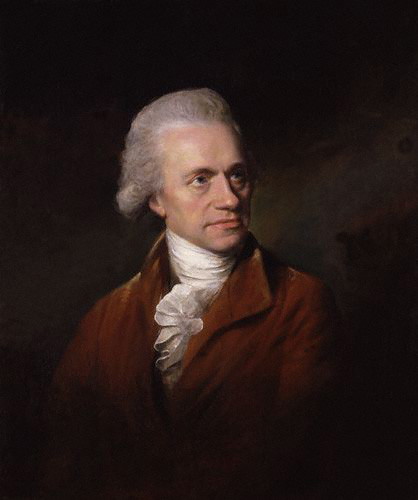

Sir William Herschel (1738-1822) was a prominent English astronomer, famous for spotting Uranus. He surveyed Mars quite extensively, examining the fluctuating size of the Martian ice caps, as well as calculating the planets diameter and length of day. He presented his ideas to the Royal Society in London in 1784. The dark areas were thought by him and his contemporaries either as water or vegetation, even forest. Some people accepted this even to the 1960’s. By using his data collected from Mars, and extrapolating Earth’s conditions, he thought he proved that there was life on mars. His argument and reasoning would dominate areology for the next century and a half.

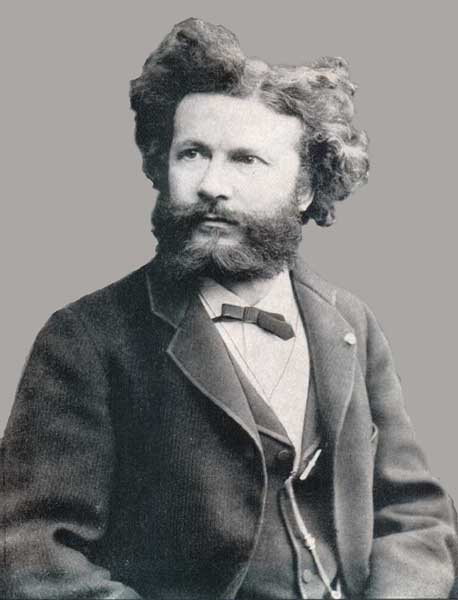

Sir William Herschel (1738-1822) was a prominent English astronomer, famous for spotting Uranus. He surveyed Mars quite extensively, examining the fluctuating size of the Martian ice caps, as well as calculating the planets diameter and length of day. He presented his ideas to the Royal Society in London in 1784. The dark areas were thought by him and his contemporaries either as water or vegetation, even forest. Some people accepted this even to the 1960’s. By using his data collected from Mars, and extrapolating Earth’s conditions, he thought he proved that there was life on mars. His argument and reasoning would dominate areology for the next century and a half. Giovanni Schiaparalli (1835-1910) initially only named the “continents” and “oceans” of Mars, more or less following his predecessors. However, his 1877-78 (during Mar’s opposition) observations estranged Mars and analogies between it and Earth further than ever before by drawing linear structures that he labelled as canali. Although the term was employed to avoid lengthy description and to give it an air of ambiguity, the resulting dispute would complicate matters anyway. One reason why Schiapaerlli thought that intelligent life may exist on Mars is due it cooling faster than Earth (which is consistent with the Nebular Hypothesis). Therefore, life would have had a longer time to develop there. Despite what seemed to be strong evidence for possible life at the time, Schiaparelli was still self-critical, and not certain of his conclusion (unlike Lowell). Nevertheless, he was still hopeful that the canali were not optical illusions and occasionally speculated too far.

Giovanni Schiaparalli (1835-1910) initially only named the “continents” and “oceans” of Mars, more or less following his predecessors. However, his 1877-78 (during Mar’s opposition) observations estranged Mars and analogies between it and Earth further than ever before by drawing linear structures that he labelled as canali. Although the term was employed to avoid lengthy description and to give it an air of ambiguity, the resulting dispute would complicate matters anyway. One reason why Schiapaerlli thought that intelligent life may exist on Mars is due it cooling faster than Earth (which is consistent with the Nebular Hypothesis). Therefore, life would have had a longer time to develop there. Despite what seemed to be strong evidence for possible life at the time, Schiaparelli was still self-critical, and not certain of his conclusion (unlike Lowell). Nevertheless, he was still hopeful that the canali were not optical illusions and occasionally speculated too far. Prominent French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) was critical of Schiaparelli. Flammarion saw the lines as well, but he admittedly speculated that the canali could be as a result of either intelligent design or by a veil of dense water vapor, thus creating an optical illusion.

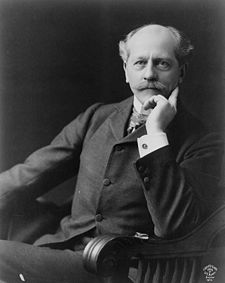

Prominent French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) was critical of Schiaparelli. Flammarion saw the lines as well, but he admittedly speculated that the canali could be as a result of either intelligent design or by a veil of dense water vapor, thus creating an optical illusion. An ardent atheist and Darwinist, Lowell (1855-1916) was excited about the possibility of life on Mars because planetary evolution on another planet would make great evidence for evolution, as well as the Nebular Hypothesis. Influenced by the Nebular Hypothesis and extrapolations by earlier astronomers, Lowell viewed Mars as a dying planet, where the inhabitants are victims of its cooling and desertification. He saw the canals (now being used interchangeably with canali) as proof of a great Martian effort to distribute water in the wake of scarcity. During what little time he was in agreement with most astronomers he helped in debunking any speculation of oceans on Mars, which gave his theory a firmer foundation. Lowell managed to popularize Mars because of its apocalyptic application to Earth (desertification), and arguing for life on Mars at this time was very popular. It was also popular because it transferred the blame from colonialism’s hand in famine and starvation to an inevitable tragedy's. His narrative style in his reports made his findings very appealing to read for upper to middle class people.

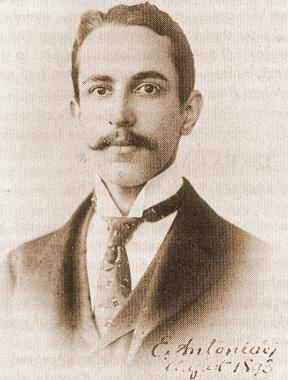

An ardent atheist and Darwinist, Lowell (1855-1916) was excited about the possibility of life on Mars because planetary evolution on another planet would make great evidence for evolution, as well as the Nebular Hypothesis. Influenced by the Nebular Hypothesis and extrapolations by earlier astronomers, Lowell viewed Mars as a dying planet, where the inhabitants are victims of its cooling and desertification. He saw the canals (now being used interchangeably with canali) as proof of a great Martian effort to distribute water in the wake of scarcity. During what little time he was in agreement with most astronomers he helped in debunking any speculation of oceans on Mars, which gave his theory a firmer foundation. Lowell managed to popularize Mars because of its apocalyptic application to Earth (desertification), and arguing for life on Mars at this time was very popular. It was also popular because it transferred the blame from colonialism’s hand in famine and starvation to an inevitable tragedy's. His narrative style in his reports made his findings very appealing to read for upper to middle class people.  E.M. Antoniadi (1870-1944) at first supported Lowell’s canals, but upon observing Mars in its opposition in 1909, he began to think that they were merely optical illusions. He in fact attempted to openly discredited Lowell. No longer believing in an elder, struggling Martian civilization, he thought life existed on Mars within the dark spots, especially lichen plant life. In other words, his view of Mars consists of a planet not dissimilar from Earth. His vision of arid Martian chaparral impacted science fiction increasingly as Lowell’s canal theory fell a little out of favor with some writers.

E.M. Antoniadi (1870-1944) at first supported Lowell’s canals, but upon observing Mars in its opposition in 1909, he began to think that they were merely optical illusions. He in fact attempted to openly discredited Lowell. No longer believing in an elder, struggling Martian civilization, he thought life existed on Mars within the dark spots, especially lichen plant life. In other words, his view of Mars consists of a planet not dissimilar from Earth. His vision of arid Martian chaparral impacted science fiction increasingly as Lowell’s canal theory fell a little out of favor with some writers.