|

Back to Holy Science Fiction! Home Page

|

|

4. In this fourth division

of Holy Science Fiction, God takes on a more universal role. In these

stories there is usually a  pantheistic

notion of God; either an almost Buddhist concept of a coalescence of minds,

or a Spinozistic universe.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s

End (1954), aliens known as the Overlords come to Earth and mandate

peace. And although Clarke insists that any religious symbolism is

“entirely accidental,” the novel is loaded with spiritual imagery.

For example, the Overlords resemble the traditional Christian image of Satan

(that explanation alone is worth reading the novel). In the end, the

reader finds out that the Overlords have come to help the next generation

of children take the next evolutionary step. That step includes the

children pantheistic

notion of God; either an almost Buddhist concept of a coalescence of minds,

or a Spinozistic universe.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s

End (1954), aliens known as the Overlords come to Earth and mandate

peace. And although Clarke insists that any religious symbolism is

“entirely accidental,” the novel is loaded with spiritual imagery.

For example, the Overlords resemble the traditional Christian image of Satan

(that explanation alone is worth reading the novel). In the end, the

reader finds out that the Overlords have come to help the next generation

of children take the next evolutionary step. That step includes the

children merging with the Overmind, a superpowerful galactic entity. In the

story it is said that God has been disproved through science and discovery,

but the Overmind resembles what many would label as God.

The French author Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin wrote about a similar phenomenon that he labeled the

“noosphere.” The noosphere is a type of planetary consciousness that

all of the organisms of the planet are directly connected to. This

idea is echoed in a lot of the spirituality that permeates much of cyberpunk.

Much of cyberpunk is filled with the idea of transhumanism and the “singularity,”

the point at which an artificial intelligence is created that is greater

than our own

merging with the Overmind, a superpowerful galactic entity. In the

story it is said that God has been disproved through science and discovery,

but the Overmind resembles what many would label as God.

The French author Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin wrote about a similar phenomenon that he labeled the

“noosphere.” The noosphere is a type of planetary consciousness that

all of the organisms of the planet are directly connected to. This

idea is echoed in a lot of the spirituality that permeates much of cyberpunk.

Much of cyberpunk is filled with the idea of transhumanism and the “singularity,”

the point at which an artificial intelligence is created that is greater

than our own  that

eventually unites all organisms (or at least, computers).

The idea of a universal power was popularized by

a somewhat well-known man named George Lucas. His idea of “the

force” in his Star Wars movies is very spiritual and mystical.

5. The fifth division of Holy Science Fiction is a more

traditional look at God and religion through the lens of science fiction. This doesn't

necessarily mean that everything in the stories agrees with any particular

religion, but the overall idea is one that suggests that our traditional

idea of God is not that far off. Typically these stories champion

the idea that there is a very strong supernatural component to the

universe we live in.

In Camille

Flammarion's novel Lumen (1864), there is a series of

dialogues between a man and a disembodied spirit. that

eventually unites all organisms (or at least, computers).

The idea of a universal power was popularized by

a somewhat well-known man named George Lucas. His idea of “the

force” in his Star Wars movies is very spiritual and mystical.

5. The fifth division of Holy Science Fiction is a more

traditional look at God and religion through the lens of science fiction. This doesn't

necessarily mean that everything in the stories agrees with any particular

religion, but the overall idea is one that suggests that our traditional

idea of God is not that far off. Typically these stories champion

the idea that there is a very strong supernatural component to the

universe we live in.

In Camille

Flammarion's novel Lumen (1864), there is a series of

dialogues between a man and a disembodied spirit.  Lumen,

the spirit, speaks of everything from death to the implications of the finite

velocity of light. From the very beginning of the story, the existence

of a soul is intertwined with a self-proclaimed scientific view of the universe.

Flammarion was a French astronomer deeply interested in both his scientific

knowledge and his religious faith. Lumen is all about divine

science and the spiritual cosmos.

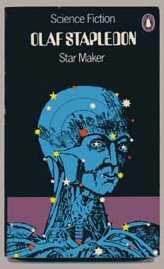

In Star Maker (1937)

by Olaf Stapledon, the reader is given a history of the cosmos that "...culminates

in a vision of God the scientist, constantly experimenting with Creation"

(Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. page 1000).

The main character is confronted by the Star Maker Lumen,

the spirit, speaks of everything from death to the implications of the finite

velocity of light. From the very beginning of the story, the existence

of a soul is intertwined with a self-proclaimed scientific view of the universe.

Flammarion was a French astronomer deeply interested in both his scientific

knowledge and his religious faith. Lumen is all about divine

science and the spiritual cosmos.

In Star Maker (1937)

by Olaf Stapledon, the reader is given a history of the cosmos that "...culminates

in a vision of God the scientist, constantly experimenting with Creation"

(Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. page 1000).

The main character is confronted by the Star Maker and he sees that “...the Star Maker was now revealed as more than the creative

and therefore finite spirit. He now appeared as the eternal and perfect

spirit which comprises all things and all times, and contemplates timelessly

the infinitely diverse host which it comprises” (Stapledon 413). Stapledon

wanted to get rid of the anthropomorphic aspects of the Christian religion,

but preserve cosmic purpose at the same time.

Other stories in this category are Marie Corelli's A

Romance of Two Worlds (1886), Edgar Fawcett's The Ghost of Guy

Thyrle (1895), and "The Hobbyist" (1947) by Eric Russell.

6. The sixth division of Holy Science Fiction is

labeled "Shaggy God" stories. Typically, Shaggy God stories deal

with Old Testament stories (predominantly the creation stories), but I

have also included some New Testament Shaggies. I will refer to the

New Testament related stories as Messianic stories.

In A.E. Van Vogt's "Ship

of Darkness" (1947), the reader finds that there are two survivors

to a space disaster who land

and he sees that “...the Star Maker was now revealed as more than the creative

and therefore finite spirit. He now appeared as the eternal and perfect

spirit which comprises all things and all times, and contemplates timelessly

the infinitely diverse host which it comprises” (Stapledon 413). Stapledon

wanted to get rid of the anthropomorphic aspects of the Christian religion,

but preserve cosmic purpose at the same time.

Other stories in this category are Marie Corelli's A

Romance of Two Worlds (1886), Edgar Fawcett's The Ghost of Guy

Thyrle (1895), and "The Hobbyist" (1947) by Eric Russell.

6. The sixth division of Holy Science Fiction is

labeled "Shaggy God" stories. Typically, Shaggy God stories deal

with Old Testament stories (predominantly the creation stories), but I

have also included some New Testament Shaggies. I will refer to the

New Testament related stories as Messianic stories.

In A.E. Van Vogt's "Ship

of Darkness" (1947), the reader finds that there are two survivors

to a space disaster who land  on

a strange alien planet. In the final line it is revealed that their

names are Adam and Eve. In Earthdoom! (1987) by David Langford

and John Grant, the Big Bang is started by a time traveler on accident.

Asimov's The Last Question (mentioned in the first division) could

very well be considered a Shaggy God story because of the final line of

the story: "Let there be light!"

Other popular stories in the Old Testament Shaggy God

tradition include The Unknown Assassin by Hank Janson, "Another

World Begins" by Nelson Bond, and "The Seesaw" by A.E. Van Vogt.

New Testament Shaggy God stories, or Messianic stories,

were and are very popular in science fiction. These stories are

usually a variant on the Christ story. They typically concentrate on

either his birth, death or crucifixion.

In Ray Bradbury's "The

Man" (1949), "space disciples" travel with Jesus on his multi-planet

crusade of salvation. The good on

a strange alien planet. In the final line it is revealed that their

names are Adam and Eve. In Earthdoom! (1987) by David Langford

and John Grant, the Big Bang is started by a time traveler on accident.

Asimov's The Last Question (mentioned in the first division) could

very well be considered a Shaggy God story because of the final line of

the story: "Let there be light!"

Other popular stories in the Old Testament Shaggy God

tradition include The Unknown Assassin by Hank Janson, "Another

World Begins" by Nelson Bond, and "The Seesaw" by A.E. Van Vogt.

New Testament Shaggy God stories, or Messianic stories,

were and are very popular in science fiction. These stories are

usually a variant on the Christ story. They typically concentrate on

either his birth, death or crucifixion.

In Ray Bradbury's "The

Man" (1949), "space disciples" travel with Jesus on his multi-planet

crusade of salvation. The good guys in Behold the Man! (1966) and Cross of Fire (1982), (by

Michael Moorcock and Barry Malzberg respectively) must actually "...become

Christ and suffer crucifixion in search of redemption for themselves"

(Clute 1002). Other Messianic stories include Theodore Sturgeon's

Godbody, Edward Wellen's "Seven Days Wonder," and Phillip

K Dick's The Divine Invasion.

guys in Behold the Man! (1966) and Cross of Fire (1982), (by

Michael Moorcock and Barry Malzberg respectively) must actually "...become

Christ and suffer crucifixion in search of redemption for themselves"

(Clute 1002). Other Messianic stories include Theodore Sturgeon's

Godbody, Edward Wellen's "Seven Days Wonder," and Phillip

K Dick's The Divine Invasion.

|

pantheistic

notion of God; either an almost Buddhist concept of a coalescence of minds,

or a Spinozistic universe.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s

End (1954), aliens known as the Overlords come to Earth and mandate

peace. And although Clarke insists that any religious symbolism is

“entirely accidental,” the novel is loaded with spiritual imagery.

For example, the Overlords resemble the traditional Christian image of Satan

(that explanation alone is worth reading the novel). In the end, the

reader finds out that the Overlords have come to help the next generation

of children take the next evolutionary step. That step includes the

children

pantheistic

notion of God; either an almost Buddhist concept of a coalescence of minds,

or a Spinozistic universe.

In Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s

End (1954), aliens known as the Overlords come to Earth and mandate

peace. And although Clarke insists that any religious symbolism is

“entirely accidental,” the novel is loaded with spiritual imagery.

For example, the Overlords resemble the traditional Christian image of Satan

(that explanation alone is worth reading the novel). In the end, the

reader finds out that the Overlords have come to help the next generation

of children take the next evolutionary step. That step includes the

children merging with the Overmind, a superpowerful galactic entity. In the

story it is said that God has been disproved through science and discovery,

but the Overmind resembles what many would label as God.

The French author Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin wrote about a similar phenomenon that he labeled the

“noosphere.” The noosphere is a type of planetary consciousness that

all of the organisms of the planet are directly connected to. This

idea is echoed in a lot of the spirituality that permeates much of cyberpunk.

Much of cyberpunk is filled with the idea of transhumanism and the “singularity,”

the point at which an artificial intelligence is created that is greater

than our own

merging with the Overmind, a superpowerful galactic entity. In the

story it is said that God has been disproved through science and discovery,

but the Overmind resembles what many would label as God.

The French author Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin wrote about a similar phenomenon that he labeled the

“noosphere.” The noosphere is a type of planetary consciousness that

all of the organisms of the planet are directly connected to. This

idea is echoed in a lot of the spirituality that permeates much of cyberpunk.

Much of cyberpunk is filled with the idea of transhumanism and the “singularity,”

the point at which an artificial intelligence is created that is greater

than our own  that

eventually unites all organisms (or at least, computers).

The idea of a universal power was popularized by

a somewhat well-known man named George Lucas. His idea of “the

force” in his Star Wars movies is very spiritual and mystical.

5. The fifth division of Holy Science Fiction is a more

traditional look at God and religion through the lens of science fiction. This doesn't

necessarily mean that everything in the stories agrees with any particular

religion, but the overall idea is one that suggests that our traditional

idea of God is not that far off. Typically these stories champion

the idea that there is a very strong supernatural component to the

universe we live in.

In Camille

Flammarion's novel Lumen (1864), there is a series of

dialogues between a man and a disembodied spirit.

that

eventually unites all organisms (or at least, computers).

The idea of a universal power was popularized by

a somewhat well-known man named George Lucas. His idea of “the

force” in his Star Wars movies is very spiritual and mystical.

5. The fifth division of Holy Science Fiction is a more

traditional look at God and religion through the lens of science fiction. This doesn't

necessarily mean that everything in the stories agrees with any particular

religion, but the overall idea is one that suggests that our traditional

idea of God is not that far off. Typically these stories champion

the idea that there is a very strong supernatural component to the

universe we live in.

In Camille

Flammarion's novel Lumen (1864), there is a series of

dialogues between a man and a disembodied spirit.  Lumen,

the spirit, speaks of everything from death to the implications of the finite

velocity of light. From the very beginning of the story, the existence

of a soul is intertwined with a self-proclaimed scientific view of the universe.

Flammarion was a French astronomer deeply interested in both his scientific

knowledge and his religious faith. Lumen is all about divine

science and the spiritual cosmos.

In Star Maker (1937)

by Olaf Stapledon, the reader is given a history of the cosmos that "...culminates

in a vision of God the scientist, constantly experimenting with Creation"

(Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. page 1000).

The main character is confronted by the Star Maker

Lumen,

the spirit, speaks of everything from death to the implications of the finite

velocity of light. From the very beginning of the story, the existence

of a soul is intertwined with a self-proclaimed scientific view of the universe.

Flammarion was a French astronomer deeply interested in both his scientific

knowledge and his religious faith. Lumen is all about divine

science and the spiritual cosmos.

In Star Maker (1937)

by Olaf Stapledon, the reader is given a history of the cosmos that "...culminates

in a vision of God the scientist, constantly experimenting with Creation"

(Clute, John. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. page 1000).

The main character is confronted by the Star Maker and he sees that “...the Star Maker was now revealed as more than the creative

and therefore finite spirit. He now appeared as the eternal and perfect

spirit which comprises all things and all times, and contemplates timelessly

the infinitely diverse host which it comprises” (Stapledon 413). Stapledon

wanted to get rid of the anthropomorphic aspects of the Christian religion,

but preserve cosmic purpose at the same time.

Other stories in this category are Marie Corelli's A

Romance of Two Worlds (1886), Edgar Fawcett's The Ghost of Guy

Thyrle (1895), and "The Hobbyist" (1947) by Eric Russell.

6. The sixth division of Holy Science Fiction is

labeled "Shaggy God" stories. Typically, Shaggy God stories deal

with Old Testament stories (predominantly the creation stories), but I

have also included some New Testament Shaggies. I will refer to the

New Testament related stories as Messianic stories.

In A.E. Van Vogt's "Ship

of Darkness" (1947), the reader finds that there are two survivors

to a space disaster who land

and he sees that “...the Star Maker was now revealed as more than the creative

and therefore finite spirit. He now appeared as the eternal and perfect

spirit which comprises all things and all times, and contemplates timelessly

the infinitely diverse host which it comprises” (Stapledon 413). Stapledon

wanted to get rid of the anthropomorphic aspects of the Christian religion,

but preserve cosmic purpose at the same time.

Other stories in this category are Marie Corelli's A

Romance of Two Worlds (1886), Edgar Fawcett's The Ghost of Guy

Thyrle (1895), and "The Hobbyist" (1947) by Eric Russell.

6. The sixth division of Holy Science Fiction is

labeled "Shaggy God" stories. Typically, Shaggy God stories deal

with Old Testament stories (predominantly the creation stories), but I

have also included some New Testament Shaggies. I will refer to the

New Testament related stories as Messianic stories.

In A.E. Van Vogt's "Ship

of Darkness" (1947), the reader finds that there are two survivors

to a space disaster who land  on

a strange alien planet. In the final line it is revealed that their

names are Adam and Eve. In Earthdoom! (1987) by David Langford

and John Grant, the Big Bang is started by a time traveler on accident.

Asimov's The Last Question (mentioned in the first division) could

very well be considered a Shaggy God story because of the final line of

the story: "Let there be light!"

Other popular stories in the Old Testament Shaggy God

tradition include The Unknown Assassin by Hank Janson, "Another

World Begins" by Nelson Bond, and "The Seesaw" by A.E. Van Vogt.

New Testament Shaggy God stories, or Messianic stories,

were and are very popular in science fiction. These stories are

usually a variant on the Christ story. They typically concentrate on

either his birth, death or crucifixion.

In Ray Bradbury's "The

Man" (1949), "space disciples" travel with Jesus on his multi-planet

crusade of salvation. The good

on

a strange alien planet. In the final line it is revealed that their

names are Adam and Eve. In Earthdoom! (1987) by David Langford

and John Grant, the Big Bang is started by a time traveler on accident.

Asimov's The Last Question (mentioned in the first division) could

very well be considered a Shaggy God story because of the final line of

the story: "Let there be light!"

Other popular stories in the Old Testament Shaggy God

tradition include The Unknown Assassin by Hank Janson, "Another

World Begins" by Nelson Bond, and "The Seesaw" by A.E. Van Vogt.

New Testament Shaggy God stories, or Messianic stories,

were and are very popular in science fiction. These stories are

usually a variant on the Christ story. They typically concentrate on

either his birth, death or crucifixion.

In Ray Bradbury's "The

Man" (1949), "space disciples" travel with Jesus on his multi-planet

crusade of salvation. The good guys in Behold the Man! (1966) and Cross of Fire (1982), (by

Michael Moorcock and Barry Malzberg respectively) must actually "...become

Christ and suffer crucifixion in search of redemption for themselves"

(Clute 1002). Other Messianic stories include Theodore Sturgeon's

Godbody, Edward Wellen's "Seven Days Wonder," and Phillip

K Dick's The Divine Invasion.

guys in Behold the Man! (1966) and Cross of Fire (1982), (by

Michael Moorcock and Barry Malzberg respectively) must actually "...become

Christ and suffer crucifixion in search of redemption for themselves"

(Clute 1002). Other Messianic stories include Theodore Sturgeon's

Godbody, Edward Wellen's "Seven Days Wonder," and Phillip

K Dick's The Divine Invasion.