Analysis |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

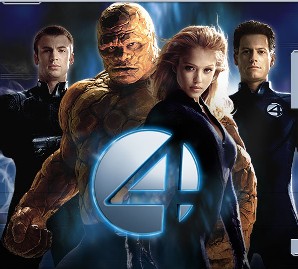

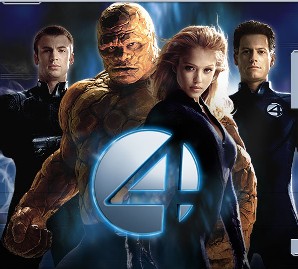

Genetic Mutations and the Creation of a Hero Although the films appeal to audiences primarily for their action-packed, thrilling battles and colorful characters, the X-Men, Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four films provide insight about the nature of how humanity regards superheroes created from science. When people look past the special effects, the films address the significance of the superheroes gaining their powers from mutations. Genetic mutations are an effective tool for creating superheroes because using science instead of fantasy to create superpowers is more believable and identifiable for people, and people can extrapolate the consequences of biotechnology impacting humanity’s genetics. The superheroes in X-Men, Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four are created from freak accidents or from evolution, so audiences can more easily see themselves as the heroes from the films. Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four characters go through an adjustment process and learn how to control and find meaning for the use of their mutations. One could argue that portraying the intervention of science as a way to gain extraordinary powers is a promotion of the possibilities of biotechnology and science. The superheroes allow people to see what the possibilities of science could do to people, in the most fantastical way possible: What if altering people’s genetics can give them the ability to transcend their capabilities and have “powers”? The role that mutant superheroes play in literature and film is they entertain people’s subconscious desire to have their own “superpowers” and shows ordinary humans who, with science, transcend human physical restraints and seemingly attain their greatest fantasies: “There is the wish for characteristics of invulnerability in ourselves which we understood well as children. Freud reminds us that these wishes (such as, for example, the ability to fly or remain invisible) are not only endemic to childhood fantasy, but remain with us in our unconscious. Also embedded in the netherworld of our unconscious is our constant propensity to return to a state of primary narcissism” (Peaslee 3). For example, Peter Parker finally attains strength, muscle, good looks, and fame for his mutant powers. Johnny Storm is another example of a mutant who uses his powers to fulfill his fantasies of fame and fortune. The use of genetic mutations as a means to create a hero is also important because mutants are almost human, but they are regarded as alien or as half-gods because of their strange appearances or powers. The mutant heroes reflect the unconscious desires of the rest of humanity because even with altered DNA, the mutants still have needs that are universal. Mutations are portrayed in X-Men, Spider-Man, and the Fantastic Four as a way to both inhibit as well as help the characters with their fundamental, human needs. One need that is shared by all of the superheroes in X-Men, Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four is the need to belong. In the case of these films, science serves to hinder the characters’ ability to belong in non-mutant society. The X-Men strongly desire to make peace with humans because they want to belong and find a place in the world again instead of going into hiding. Spider-Man, although his desire to belong originates before he becomes a mutant, is confused about his role in society because people have a love-hate relationship with his superhero alter-ego, and he struggles finding stability in his everyday life. The character Johnny Storm and Ben Grimm in the Fantastic Four represent the unconscious need to belong in two ways. Storm’s extreme enthusiasm to absorb all of the attention he can get due to his mutation shows the human desire to be loved and awed by others. He represents humanity’s need to be recognized for its worth. Grimm, on the other hand, shows his desire to belong in the world again by his persistence to get rid of his mutation as soon as possible. Besides the inherent longing to fit in with a community, the use of mutants as superheroes addresses the internal struggle to battle the problems of the world as well as one’s own problems. The fact that humans are transformed into mutants who are responsible for saving the world from evil shows how, “the role of the superhero in cultural texts is one which functions in a particularly multinodal fashion, illustrating conflicts within the social sphere while expressing at the same time eminently individual and unconscious desires and needs” (Peaslee 2). The superheroes in X-Men. Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four are faced with the same desires for humanity: justice, peace, and the end of evil. This consistent motivation to use mutations for good is what makes these mutants heroes, and these desires drives Spider-Man, The X-Men under Dr. X, and the Fantastic Four to continue serving society with their powers. The way the rest of the world in the X-Men, Spider-Man, and Fantastic Four films responds to mutants gives strong implications about the dangers of the intervention of science to give humans superpowers: “Superhero genre implies a profound uneasiness in us about science and its prodigious, morally neutral power” (Mano 566). On the flip side of fulfilling people’s need of transcending the human condition, these films are cautionary about the potential backlash people can have against who fear genetically altered humans: “Superheroes are less bizarre than one might suppose: each is an apposite symbol of the human condition” (Mano 567). Mutations that fundamentally change people’s DNA causes the public in Spider-Man (1 and 2) and X-Men (1 and 2) to fear and hate them because they represent all that is considered “not-human,” abnormal, or the unknown. These films imply that a part of the human condition is to fear the unknown, or to fear the intervention of science and human capabilities. Therefore, the super-mutants, who used to be human, are forced to abandon the luxuries of their old world and hide their identities to prevent the risk of being persecuted and/or alienated. Because of the natural xenophobia the non-mutants have against mutants in these stories, the characters respond differently, which often differentiates the “good mutants” from the “bad mutants.” In the X-Men movies, Dr. X tries to work with humans and get them to understand that mutants deserve fair treatment, while Magneto wants to destroy humans for their intolerance towards mutants. Ben Grimmm from Fantastic Four rejects society because he is regarded as a monster for his mutation. In the Spider-Man films, Parker is conflicted multiple times about whether he should continue fighting for a society that gives him bad publicity and doesn’t appreciate him. The article “Super Freaks” by Keith Mano also analyzes how the use of genetic mutations to create superheroes has a back-lash on the definition of a “hero” to begin with. Instead of purely arguing that mutations cause a variety of social consequences on superheroes, he argues that scientifically-created heroes lack meaning in comparison to heroes from religious or mythical origin: “No friendly Omnipotence exists to be propitiated or loved or saved by. Events have their scientific cause” (Mano 567). He criticizes the more modern-age of heroes and claims, “Marvel Supers are a synecdoche for our faithless age” (Mano 566). He implies that genetic mutations only give people the technology to fight against evil, but no real purpose or reason to be a hero. Because the heroes are not divine, rather they are humans who fortuitously acquired super-human qualities, then the value of what the hero stands for and represents in the battle against evil diminishes. For example, he uses the X-Men as a reference, saying, “But why is Magneto bad, Cyclops good? No reason. We depend on super whims” (Mano 567). He makes an interesting point about how the role of mutations may provide a scientific explanation for superpowers, but it provides no moral, meaningful explanation as to why a particular person has been selected to have powers that fight for justice. He claims the supervillains exist purely to counter-balance the superhero in a competition against each other’s mutant powers, neutral of a real reason behind the conflict. I would argue that the fact the superheroes are not divine, rather they are ordinary human beings, is what makes these superheroes so extraordinary. The intervention of science does not make the person a hero; genetic alterations give people the opportunity to use their powers for selfish reasons, to save others, or to deny them and not use them at all. No one knows if the characters in X-Men, Spider-Man, and the Fantastic Four were destined to be heroes or not, so what makes characters like Peter Parker, Reed Richards, and Dr. Xavier heroes is that they chose live as mutants so they can use their powers to defend weaker humans from evil. Just because their powers were given to them “on a whim” does not take away the meaning of their heroism. Science influences the human body to have superpowers, but the inherent desire to help other people and sacrifice one’s freedom to do so is a choice that humans, both mutants and non-mutants, can make.

|